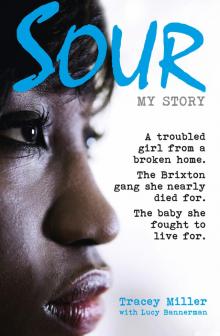

Sour Read online

Copyright

Certain details in this book, including names, places and dates, have been changed to protect those concerned. Some events have been dramatised

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road,

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperElement 2014

FIRST EDITION

© Tracey Miller and Lucy Bannerman 2014

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014

Cover photograph © Kazunori Nagashima/Getty Images (posed by model)

Tracey Miller and Lucy Bannerman assert the moral

right to be identified as the authors of this work

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780007565047

Ebook Edition © August 2014 ISBN: 9780007565054

Version 2014-07-29

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Mum and Dad

The Estate

Gangland

Islam

I’m Gonna Be a Name

Dick Shits

Steaming

Real Gangs

Meeting the Youngers

Welcome to the Younger 28s

The Secret

Entertainment

High Life

Kitchen Drawer

Mysteries

Right Girl, Wrong Crime

Getting in Deeper

Betrayal

The Art of Stabbing

Playing Hardball

Yout Club

In For a Shock

Holloway

Safe Haven

Change of Occupation

Going Professional

Losing It

David

Inshallah

No Such Thing as Justice

The Mosque

The Raid

Riots

Point of No Return

Overdose

Shock

Epilogue

A Note From Montana

A Note From Brooke Kinsella

Exclusive sample chapter

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter

About the Publisher

Acknowledgements

A big thank-you to my editors Vicky Eribo and Carolyn Thorne; my literary agent Jessie Botterill; my wonderful co-author Lucy Bannerman and the rest of the team at HarperCollins.

A special thank-you to my mum, for giving me life – I Love You! My brother, my sisters, my nieces, my family, who have always been there for me. My two daughters who keep me focused – I love you both dearly. Not forgetting my close friends who have kept me strong in one way or another.

A final thank-you to Brooke Kinsella, Hellie Ogden, Temi Mwale, Elijah ‘Jaja’ Kerr and Saadiya Ahmed.

Introduction

They call me Sour. The opposite of sweet. Shanking, steaming, robbing – I did it all, rolling with the Man Dem.

I did it because I was bad. I did it because I had heart. And the reason I reckon I got away with it for so long? Because I was a girl.

Sour was my brand-name. How should I put this? I was quite influential round my endz. In my tiny, warped world, where rude boys were the good boys and exit routes non-existent, I was top dog. I want to give people outside the lifestyle some insight into lives like mine. I want parents to think about what their kids really get up to. For them, let this be an education, an eye-opener.

I want to lay myself bare to all the people who knew me when I was bad. I am not offering this as an excuse. I’m offering an explanation.

Above all, for all the youngers like me, the kids without a home who become kids without a conscience, the ones living the streetlife who know the thrill of likking the tills or steaming a shop, the young bucks who don’t need to be told how easily a blade slides out of punctured flesh, let this be a warning.

Youth workers could argue I had no chance. Politicians could blame my parents. Others might say the choices I made were mine and mine alone. Maybe they’re all right.

Me? I think badness is genetic. With a manic depressive for a mother and a convicted rapist for a father, I ain’t never gonna be Little Bo Peep.

So this is my story, the real story of how I fell down the rabbit hole of gangland. There are no real excuses. I did what I did and I live with what happened. I have a lot to be thankful for.

The hard part is not working out where it all went wrong. The hard part is making it right.

Mum and Dad

My mum’s first memory of her childhood in Jamaica begins with a broom. Mum was eight; her little sister, Rosie, must have been five. They lived in Kingston, in a one-bedroom shack with their nana.

“Yuh pickney have tings easy,” she always used to tell us. “When we did young we had to work fucking hard to keep the yard clean bwoy, wash fi we own clothes and dem ting dere, cook our own food and ting. None ah dis mordern shit, yuh ah gwarn wid.”

It was the day before Christmas. Mum was outside, scrubbing the yard. She had left Rosie dancing in the dust by the stove, a skinny girl grappling with a broom twice her size. Mum was down on her knees with a scrubbing brush, when she heard the screams.

She’d knocked over the pot of bubbling oil that had been cooking on the stove.

“Burned all the hair clean aff her head,” she’d say. “Her little dress stuck to her skin.”

Mum, still such a small child herself, rushed for scissors to cut the cotton from the blistering skin and tried to calm the hysterical girl, but it was too late. Boiling oil is too strong an adversary for five-year-old girls.

At the funeral, she arranged the pillow in her coffin to make sure she was comfortable.

“Me did do her hair real nice fi church, well, what was left ah it,” she said.

They buried her on Christmas Day.

Her own mother didn’t make it to the church that day. She had already long left Kingston, leaving behind her daughters with their grandmother, to chase the tailwinds of the Windrush Generation to the UK.

No one had heard from her mother, but there was a rumour she’d found a job in an office. Mum said she spent years in that old, broken-down yard, waiting for the day she would send for her to join her.

While she waited, her grandmother started taking on lodgers.

That’s her other memory – of the lodger. He worked in the garage during the day, and drank beer from his bed by night. He persuaded her to go away with him one afternoon after school, and took her to the cemetery.

“The bloodclart smelled of grease and chicken fat. Laid me on a tombstone and put his finger up me.”

Lord have mercy, things weren’t right in that house. I never met Mum’s grandmother, but maybe that’s for the best – I have a feeling me and her wouldn’t have got on.

She was too strict for a start. No loitering after scho

ol, no free time, no fun.

She would tell my poor mum, “When school done, if mi spit pon de floor, yuh better reach home before it dry.”

If not, a beating was waiting. I didn’t believe Mum when she told me about the grater.

“She put a grater in the yard, till it got hot, hot, hot in di sun.”

Then she’d make Mum kneel on it. Oh my days, what a wicked witch! I’d have put that grater where the sun don’t shine.

Weird thing is, my mum still sticks up for the woman who raised her.

“Cha man, her heart did inna di right place.”

And where exactly would that be?

Still, I’ll give her something. She taught my mum to cook all the hardcore soul food that me and my brother love. Chicken, rice and peas, all the meats – no one cooks it better than my mum.

Aged 12, Mum finally got the call. Her mother finally sent a plane ticket for London. She said in the letter she was doing well and life was good. Mum dreamed of a big house with servants. She dreamed of the high life, in a country where people drove shining cars, girls wore short skirts and their wallets overflowed with Queen’s head.

But Brixton in the early 1970s wasn’t quite the paradise she’d imagined. For starters, she stepped off the plane in a cheap, yellow dress and was welcomed by snow. It pretty much got worse from there.

“In Jamaica we went to church because we suffered so much,” she said. “When we came to London, nobody went to church no more.”

“Me did know seh dere was a God in Kingston, becah he used to answer my prayers. Nobody nah answer no prayers inna Brixton.”

Oh yeah, quite a character, my mum. On her good days, she likes watching EastEnders, Coronation Street and Al Jazeera.

Whenever there’s something on the news about “feral youths”, as all those suited-and-tied BBC broadcasters like to call ’em, she always shakes her head and mutters, “Yuh pickney haffi learn to rass.”

Or, in other words, people’s kids need to learn to behave.

She loves baking, and makes a mean Jamaican punch. Oh my days! Nestlé milk mixed with pineapple juice, nutmeg, vanilla, ice cubes. Mix in rum or brandy and you’ve got a wicked pineapple punch. And a good chance of getting Type 2 diabetes, just like her.

I know I shouldn’t laugh, because of her illness, but there were wild times too.

Like that time she insisted on driving me and my brother to school in her speedy little Ford Capri, instead of letting us take the bus.

“Hold on!” she screamed, leaning back and putting one arm across my brother in the front seat and one arm on the steering wheel, as she slammed down her foot on the accelerator.

“Me taking di kids to school!”

She whizzed down Coldharbour Lane that day like she was bloody Nigel Mansell, cutting up cars and swerving wildly down the street. I remember screaming as we jumped the red lights and brought a big-assed bus screeching to a halt. She crashed into a van and folded up the front of the car. Mum didn’t even notice.

She just turned the radio up full volume and started chanting whatever weird shit came into her head. Oh my days, it was like Mrs Doubtfire meets Grand Theft Auto.

Yusuf and I clung on to our seatbelts and just prayed to God to get there safely. I swear I’ve never been so happy to get to school.

“Me go pick yuh up later,” she shouted, depositing the pair of us, shaking, traumatised heaps at the no-parking zone by the gates. “Make sure yuh did deh when me reach at tree tirty!”

With that, we heard the wheels spin, the engine roar, then she was gone.

Lo and behold, 3.30pm came and went, but Mum and her Ford Capri were nowhere to be seen.

The policeman told us later they had to give high-speed chase through Brixton.

“Rassclat!” she said, when we told her what happened. “Me did what? Yuh sure? I just remember seh me ah drive tru traffic, me put dung me foot annah drive fast, one minute me ah get weh, next minute dem got me.”

We tried not to giggle.

“Den I had to fight a whole heap ah policeman, and dem fling me down inna dem bloodclart van and take me down the station, bastards. Den dem take me go ahahspital.”

That was my first day at a police station. We spent the whole day there. They fed us, showed us the horses, the police cars. I’m not gonna lie – it was like a fun day out.

It was less fun, I imagine, for that poor Ford Capri.

She was remorseful about some things. Like the time she dangled my sister off the balcony.

“Me can’t believe seh mi woulda do dat to yuh,” she told Althea, once she came back down to earth. “I’m so sorry, girl, please forgive me, yuh mum wasn’t well.”

Althea and her always had problems after that.

Then there were the afternoons she used to pick up her baseball bat and walk through the streets, speaking to herself. Or the time she stripped stark naked and walked calmly down the road at rush hour. Or the time – this is my favourite – when she brought an elderly Russian lady home, and held her hostage.

How many other kids come home from school to find a confused and frail old woman perched on the settee, saying they’ve been kidnapped by your mum?

“Mum, what you doing?” we screamed.

“Me ah ask de woman, where ye live? And she come with me. Me haffi look after her.”

I looked at the frail old woman, clutching an untouched plate of rice and peas in her trembling hands.

Mum came into the front room, brandishing more food.

“Yuh hungry? Eat dis cake, it’s nice. Drink some tea. If yuh want, gwarn go sleep and drink.”

The sweet old lady reached up for my hand.

“Please,” she whispered, “I want to go home.”

Yusuf helped her escape, while I kept Mum distracted. She was horrified when she found the front room empty.

“Which one ah yuh let her out? Where’s she gaarn? I’m looking after her!”

Oh yeah, every year it was something, and it always seemed to be round Christmas.

You know that song, “Love and only love will solve your problems” by Fred Locks?

That’s the one she liked to listen to during her episodes. That’s the one she’d listen to over and over again and all through the night. The bass would shake the house.

Whenever that came on, and the volume was turned up, we knew to brace ourselves.

As for my dad, well, he was a proper little bad boy.

Mum’s first two babydaddies had been and gone before she met the man I have the misfortune to call my dad.

I’ve only ever known my mum as a medicated woman but she must have been an attractive lady. She could get the boys.

Althea’s dad was young too. His family were having none of it, and he soon scarpered.

Melanie’s dad, he was rich. He had money, but he was married, so Mum was his sidepiece. Not that she knew that at the time. He left her heartbroken and went back to the wife.

But me and Yusuf’s dad? Woah, Mum really hit the jackpot there.

In Brixton they called his crowd the “Dirty Dozen”. They travelled in a pack.

Marmite liked to play dominoes. Runner, Sanchez and the rest liked drinking. Irie was a school bus driver by day, getaway driver by night. There were rumours he used to lock up girls in the bathroom at parties and assault them. Charmer. Monk was sweet, the quietest of the lot, so it took them by surprise when he ran his babymother down and stabbed her one night on the way home.

Then there was ’Mingo. Short for Flamingo – when things got naughty, that man could fly away and never get caught. And, finally, in his knitted Rasta hat and moccasins was Pedro, aka Wellington Augustus Miller. Or, as I no longer call him: Dad.

He’d break Mum’s nose and black out her eyes, gamble away the wages she earned as an admin clerk in an office. He lost me a baby sister too. Kicked Mum in the belly till she dropped her in a toilet. She once ended up jumping through a glass door to escape him. Doctors said she only had a 50–50 chance if th

ey tried to remove the shards from her skull, so they left them inside. They must have done the right thing, coz she’s still here.

The X-rays revealed a freshly fractured skull, and a long, unhappy marriage’s worth of broken bones and damaged organs. I was six weeks old.

Oh yeah, he was a proper nuisance, my dad. And you know the irony? With the stepdads who followed, I still remember Mum as being the violent one.

She was working in two jobs – clerk during the day, a cleaner in the evenings – living for the weekends when she and her friends would follow the sound systems round south London, stealing drinks and befriending bouncers.

The Dirty Dozen weren’t Yardies. They weren’t in that league. Sure, they’d beat up an ice-cream van man with a chain, but their crime wasn’t organised, not in the way the Yardies’ was.

Still, anywhere they got to was pure war.

The first night my parents met, Mum watched Dad beat up a bouncer so bad they took him to the hospital. He had taken offence at being asked to pay an entry fee.

Next time they met in the Four Aces nightclub in north London.

“He had cut off his locks, he looked like a proper gentleman,” she recalled.

Not quite gentlemanly enough, of course, to hang around for my birth.

“Not one of those fathers was by my side when I was pushing dem babies out,” she still complains, as if that was the worst they did.

He popped in and out of our lives.

We lived in and out of mother and baby units, as she moved in with him and moved out again. I remember a garden, a Housing Association house in Tooting, with pears and apples and strawberries. But the council got a bit fed up with Mr Miller’s illegal gambling nights in the front room, so we lost that too.

The punches went both ways. Dad was once lay waited outside a club, after bursting a chain off this girl’s neck. Her friends tried to attack him with a samurai sword. They were the ones who ended up in the dock. Would you believe that it was poor, innocent Wellington who took to the witness stand to testify as the victim?

It wasn’t long before he was in court again.

Sour

Sour